Margot Friedlander lived in Nazi Berlin with her mother and younger brother. It is January 20, 1943. By that time, many Jews, including some of her family and her father, had already fled Germany. The frequency of deportations to a mythical ‘East’ from which no one ever returned had increased. Living conditions had become increasingly restrictive. Since 1941, when they went out in public, they had to wear the ‘Star of David’ on their cloth to mark them as Jews. They could not sit on a bench in the park, swim in a public pool, go to the movies, or use public transportation. Jewish professionals lost their jobs. Margot’s father was a gynecologist. He was only allowed to treat Jewish patients. Margot’s brother could not go to the gymnasium because it was reserved for ‘Aryan’ Germans. Margot notes, “As 1935 progressed, the mood in Berlin became more and more depressing. We heard of arrests all the time. We passed shop windows with the words ‘Don’t buy from Jews.’” On the night of November 9-10, 1938, the Nazis organized massive violence against Jewish owned businesses and synagogues. German Jews, who felt like Germans, were unsure how far the Germans would go in oppressing them. After all, the Germans were supposed to be ‘civilized’ people who shared a culture to which the Jews had made enormous contributions. Moreover, the Germans would surely eventually stand up to the Nazis and help the Jews. Margot: “Now we saw that no one would help us. They had even cheered when the synagogues burned.” Moreover, precisely because they felt a sense of belonging to this country, many found it hard to accept the idea that for their own protection they would have to leave behind what generations had created.

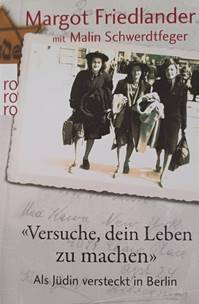

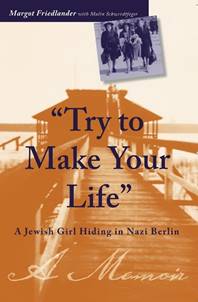

Margot’s mother could not cope with the situation. In fact, friends came to visit her in Berlin and tried to take her immediately to a police camp in East Germany. It was supposed to be a safe place, and it indeed was since everyone who had been there had survived. But she wanted to wait a little longer. Eventually she agreed to join them in a few weeks. Preparations for her move were made in secret. On January 20, 1943, a final preparatory meeting was scheduled in her apartment. Margot was walking along the sidewalk toward the entrance when she noticed an unknown man entering. As she climbed the stairs, she saw him standing with his back to the door of her apartment. She walked past him and rang the doorbell of the apartment one floor above hers. The owner told her that the Gestapo had taken away several people, including her younger brother. Thus, her mother was still free. Therefore, Margot went to a friend’s house, where her mother was supposed to wait. But she arrived too late. Her mother had already gone to the Gestapo to join her son. Before she left, she had asked that Margot receive this verbal instruction: “Try to make your life.” There was no written note. But Margot was given her handbag with an address book and her amber necklace. She never saw her mother or younger brother again. They were both murdered upon arrival at Auschwitz.

Margot was able to stay with friends for a few days. But she had to decide what to do. She had her mother’s address book. In it, she had collected the names of all the people who might be able to help them. In the end, Margot decided to go underground. She took off her ‘Da-vidstern,’ dyed her hair red, and even found a way to have her nose surgically altered. From now on she lived for days, weeks, sometimes months with people she did not know but who were willing to help her. She continued this life for 15 months, until April 1944. During this time there were many air raids. Margot could not seek shelter where she lived because other people in the house would have wondered who she was. Instead, she used a public air-raid shelter. On one such occasion, she had stayed in such a shelter with two friends. On their way home, two men stopped them and asked for identification. Of course, Margot had no identification. It turned out that the two men were “Greifer,” Jews who hunted down other Jews living underground to hand them over to the Gestapo. They saw this as their way of protecting their own families and themselves from deportation. Margot admitted that she was Jewish.

At the transit camp in Berlin, Margot realized that she had only two options. Either she was sent ‘to the East’ or to the Theresienstadt ghetto. “Those were the two ways we could leave this transit camp. We knew nothing about the East. We heard more about Theresienstadt.” Many well-known Jews were sent there. At the end of May 1944, another transport was organized to go there. But there were only 23 people on the list. Margot’s name was not on it. She had made the acquaintance of a man who worked in the camp administration and who had promised to help her. So, she approached him with her wish to be included in this transport. He was able to arrange it for her. In the book, her time in Theresienstadt begins on page 178.

On or about April 20, 1945, a train with many cattle cars pulled into the station. The doors opened and people who no longer looked human fell out of the wagons, many of them dead. These people came from Auschwitz. Before that extermination camp was liberated on January 27, 1945, the SS guards had sent these people on the infamous ‘death march.’ They had walked for nearly three months. Those who survived were put in cattle cars and sent to Theresienstadt. Margot writes: “At that moment, the ‘East’ became associated with a name [Auschwitz]. It was at this moment that we learned of the existence of the death camps. And at that moment I realized that I would never see my mother and my brother again.”

Soon after, Russian troops liberated Theresienstadt. Margot and her future husband tried to adjust to the new circumstances. On June 30, 1945, her husband, Adolf Friedländer, received a telegram from his sister, Ilse, who lived in New York. In July 1946, Margot and her husband were on a ship that would take them to New York. She ends her memoir on a bitter note, wondering if the Statue of Liberty, which the ship had passed, really symbolized freedom. After all, when they desperately needed help to escape Germany, the U.S. had erected bureaucratic hurdles they could not overcome. “If I had been standing here eight years earlier with my mother and brother, I might have been happy.”

With some help by AI-powered Deepl.

Leave a comment