Chapter 1: Containment is not possible

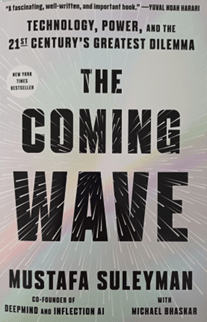

This book is about the “rise and spread of technologies” that take “the form of world-changing waves” (p. 6). According to the authors, the world is now “in an unprecedented moment of exponential innovation and upheaval, an unparalleled augmentation that will leave little unchanged” (p. 7). The drivers of this upheaval are artificial intelligence (AI) and synthetic biology. It will be impossible to stop these developments. Suleyman, of course, joins all those who have already wondered what will happen when AI can replicate human intelligence and “outperform all human cognitive abilities” (p. 8). In fact, AI, after decades of development, “looks set to reach human-level performance” (p. 9). For business, this will be good; for humans, this will be a “seismic shift” that will come with “unprecedented risks” (p. ibid.). This translates into the need for containment, and people must not fall into the “pessimism-aversion trap” (p. 13), although “the head-in-the-sand is the default ideology” (p. 15) of people working in technology development or in drafting policies.

Near the end of his introduction, Suleyman warns about “the political implications of a colossal redistribution of power engendered by an uncontained wave. The foundation of our [mainly meaning “Western,” presumably] present political order—and the most important actor in the containment of technologies—is the nation-state. Already rocked by crises, it will be further weakened by a series of shocks amplified by the wave: the potential for new forms of violence, a flood of misinformation, disappearing jobs, and the prospect of catastrophic accidents” (p. 17).

Chapter 2: Endless proliferation

Suleyman summarizes the development of previous technological waves, such as electricity or the car. Their key characteristic is “endless proliferation,” and he reminds readers that “Computing transformed society faster than anyone predicted and proliferated faster than any invention in human history” (p. 32). It was only in the late 1950s and 1960s that “Robert Noyce invented the integrated circuit at Fairchild Semiconductor” (ibid.). Both have become, I might add, almost magical points of reference for those interested in how microchips came into being. They, in turn, not only brought into being the personal computer as an everyday household item, but also enabled the emergence of the Internet. Today, “They form the very architecture of modern life” (p. 33), and computing “has become the dominant fact of contemporary civilization” (p. 34). I do not normally like hyperbole. Yet, I do not think that these statements exaggerate the effects these technological innovations have on the way we live in the first quarter of the twenty-first century.

Chapter 3: The containment problem

It is headlined “The Containment Problem.” When a technology proliferates, “chains of causality” (p. 36) become incomprehensible (as earlier happened with money; I might pay a shopkeeper for a good, but I have no control over the way he/she uses what used to be my money, and much less do I know what the third actor in this chain will do with it, producing effects I could never have foreseen at the time I made my initial purchase). So, what does “containment” mean? It is “the overarching ability to control, limit, and, if need be, close down technologies at any stage of their development or deployment. It means, in some circumstances, the ability to stop a technology from proliferating in the first place, checking the ripple of unintended consequences (both good and bad)” (p. 36). It is “a set of interlinked and mutually reinforcing technical, cultural, legal, and political mechanisms for maintaining societal control of technology during a time of exponential change” (p. 37f.). Not many examples exist for this kind of approach. Nuclear weapons is an example. The challenge of technology today is not, as in earlier epochs, to invent and apply them. Today, the issue has become how to contain an extremely powerful technology so as to ensure that “it continuous to serve us and our planet. That challenge is about to decisively escalate” (p. 48).

Chapter 4: The technology of intelligence

In this chapter, Suleyman describes “The Technology of Intelligence,” that is, AGI, or artificial general intelligence. What they had in mind was “to build truly general learning agents that could exceed human performance at most cognitive tasks” (p. 51). The second technology is synthetic biology: “For the first time core components of our technological ecosystem directly address two foundational properties of our world: intelligence and life. … No longer simply a tool, it’s going to engineer life and rival—and surpass—our own intelligence” (p. 55). In the following, the author touches on Large Language Models (such as ChatGPT). He eventually asks, “where does AI go next as the wave fully breaks?” (p. 73). After all, the current versions, though impressive, are still rather narrow. “What is yet to come is a truly general or strong AI capable of human-level performance across a wide range of complex tasks—able to seamlessly shift among them” (p. 73f; italics in the original). Don’t forget: “AI is still in an early phase” (p. 74). It still cannot deal with ambiguous tasks that require “interpretation, judgment, creativity, decision-making, and acting across multiple domains, over an extended time period” (p. 76). From this perspective, the question of whether AI can have consciousness is a distraction, because emphasis is on the development of practical capabilities. Suleyman calls the goal “artificial capable intelligence” (ACI), “the point at which AI can achieve complex goals and tasks with minimal oversight” (p. 77). ACI is seen as the next evolutionary step of AI. The author warns, “Make no mistake they [ACIs] are on their way, are already here in embryonic form” (p. 78).

Chapter 5: The technology of life

In this chapter, the author turns to synthetic biology, meaning the “convergence of biology and engineering” (p. 79). He touches on DNA scissors and CRISPR. This is about “the ability to read, edit, and now write the code of life” (p. 83). Suleyman sees the “promise of evolution by design” (p. 84). Biotech follows a similar trajectory to information technology before it. The author also reiterates a recurrent theme by saying, “No one can fully say what the consequences might be” (p. 85). Biotech might improve medical treatment capacities, improve memory, or achieve “serious physical self-modification” (p. 86). “As might many other elements of frontier technologies, it’s a legally and morally ill-defined space” (ibid.).

Chapter 6: The wider wave

This chapter is entitled “The wider wave,” indicating that AI and biotech are components of a wider wave of a technologically far-reaching transformation of human society. Suleyman deals with robotics, quantum mechanics and what he calls the “energy transition,” mainly meaning nuclear fusion. These “three technologies will dominate the next decade” (p. 101). This poses another question: “What comes after the coming wave?” (ibid.). Of course, he cannot answer this question. After all, his book is about the coming wave, and we know little about how this one will work out. Instead, he is going to “break down its [the coming wave’s] key features” (p. 102).

Chapter 7: Four features of the coming wave

Suleyman distinguishes “Four features of the coming wave” (p. 103). Three of them will impact on the “problem of containment” (p. 105). These features are asymmetry, hyper-evolution, omni-use, and autonomy. Regarding its asymmetric impact, he compares the coming wave to the introduction of the printing press, the invention of steam power and the internet. That is, asymmetrical impact is about the scale of change relative to the status quo. As usual, the positive effects are as huge as the possible risks. Moreover, “Interlinked global systems are containment nightmares. And we already live in an age of interlinked global systems. In the coming wave a single point—a given program, a genetic change—can alter everything” (p. 107; original italics).

Will the coming wave give society time to understand and adapt? Hardly, as could be seen from the internet. “The world digitized, and this dematerialized realm evolved at a bewildering pace” (p. 107f.). Hyper-evolution does not only refer to the pace of development in one specific realm, but also to the fact that it will occur in a large set of areas. Similarly, omni-use indicates that the practical fields of the application of technology are not limited to the area where they were devised. “Technologies of the coming wave are highly powerful, precisely because they are fundamentally general” (p. 111). Consequently, it “is not a priori obvious” whether an invention will be used to playing games or for “flying a fleet of bombers” (ibid.). A look to the past: “Omni-use technologies like steam or electricity have wider societal effects and spillovers than narrower technologies” (ibid.). There is a time dimension to this aspect: “Over time, technology tends towards generality. What this means is that weaponizable or harmful uses of the coming wave will be possible regardless of whether this was intended. … Anticipating the full spectrum of use cases in history’s most omni-use wave is harder than ever” (p. 112). Thus, this is the containment problem supersized” (ibid.).

However, the new wave will introduce a new problem to technological development, the potential autonomy of what used to be merely a human-controlled tool. For example, there has been much talk about autonomous cars. Also, the coming tools will have the capacity for self-improvement. Thus, the question: “We humans face a singular challenge: Will new inventions be beyond our grasp?” (p. 114). Things like CPT-4 or AlphaGo are already essentially “black boxes,” which means that the humans who created them cannot manually reconstruct in which way the machine had reached a certain output. In sum: “Nobody really knows how we can contain the very features being researched so intently in the coming wave. There comes a point where technology can fully direct its own evolution; where it is subject to recursive processes of improvement; where it passes beyond explanation; where it is consequently impossible to predict how it will behave in the wild; where in short, we reach the limits of human agency and control” (p. 116). Thus, the question: “Given risks like these, the real question is why it’s so hard to see it as anything other than inevitable” (ibid.; original italics).

Chapter 8: Unstoppable incentives

The author tries to answer this question in this chapter on “Unstoppable incentives” (p. 117). Suleyman explains five drivers that provide incentives to engage in the development of technologies that make up the coming wave. These incentive areas are predictable enough:

- National pride and strategic necessity (think about the US-China rivalry and other geopolitical relations, leading to quests for technological leadership for economic and security reasons).

- The “global research ecosystem” (p. 119) or, in other words, “knowledge just wants to be free” (p. 127), and so want to be scientists working at universities pursuing research and publications for getting tenure.

- Economic incentives: “Science has to be converted into useful and desirable products for it to truly spread far and wide. Put simply: most technology is made to earn money” (p. 132), and thus: “Anyone looking to contain it [the wave] must explain how a distributed, global, capitalist system of unbridled power can be persuaded to temper its acceleration let alone leave it on the table” (p. 134).

- “Global challenges”: from farming to climate change, energy production, that is, the use of technology to solve global problems: “… that we can meet the century’s defining challenges without new technologies is completely fanciful” (p. 140). On the other hand, one must not fall into the trap of a “naïve techno-solutionism” (p. 139).

- Ego: “Find a successful scientist or technologist and somewhere in there you will see someone driven by raw ego, spurred on by emotive impulses that might sound base or even unethical but are nonetheless an underrecognized part of why we get the technologies we do” (p. 141).

Nationalism, capitalism, science, and ego “are what propel the wave on, and these cannot be expunged or circumvented” (ibid.). Moreover, these elements interact with each other to generate effects, leading “to a complex, mutually reinforcing dynamic” (p. 142). There is only one unit that can try to undermine this dynamic: “the nation-state” (p. 143). But these nation-states are under stress already. The coming wave will collide with this kind of nation-state. “The consequences of this collision will shape the rest of the century” (ibid.).

Chapter 9: The great bargain

This chapter is headlined “The grand bargain.” It refers to the bargain between nation states, their centralization of power, and their monopoly over violence and the benefits this must have for the people living on its territory. Yet, the balance between these two sides “is fracturing, and technology is a critical driver of this historic transformation” (p. 148). Will present-day liberal-democratic nation-states be able to manage the containment of the coming wave? Suleyman notes that, “An influential minority in the tech industry not only believes that new technologies pose a threat to our ordered world of nation-states; this group actively welcomes its demise. These critics believe that the state is mostly in the way. They argue it’s best jettisoned, already so troubled it is beyond rescue. I fundamentally disagree; such an outcome would be a disaster” (p. 151).[1] This book, Suleyman writes, “in part, is my attempt to rally to its [the nation-states’] defense” (ibid.). In saying this, he refers to “fragile states” but also to reduced trust in democracy and an increased trend towards authoritarianism, which is said to be based on “social resentment” towards socio-economic inequality, resulting, among other things, in “waves of populism” (p. 154).[2] Unfortunately, “This makes containment far more complicated” (ibid.). How can consensus and agreement be reached among states “when our baseline mode seems to be instability” (ibid.)? Moreover, the technological innovations of the past few decades have amplified “political polarization and institutional fragility” (p. 155). In other words, the political systems of nation-states have already poorly dealt with the previous wave of digital innovation, allowing the forces unleashed by it to destabilize them. How can one hope that such units are equipped to handle the containment of the coming wave, which will be much more far-reaching than simple digitization was? “AI, synthetic biology, and the rest are being introduced to dysfunctional societies already rocked back and forth on technological waves of immense power. This is not a world ready for the coming wave. This is a world buckling under the existing strain” (p. 156f; original italics). Under these circumstances, some liberal democracies “will continue to be eroded from within, becoming a kind of zombie government” (p. 158). Others might become “supercharged Leviathans whose power goes beyond even history’s most extreme totalitarian governments. Authoritarian regimes may also tend towards zombie status, but equally they may double down, get boosted , become fully fledged techno-dictatorships” (ibid”. Given this perspective, the chances that there will be governments that are able to competently manage the coming wave for the greatest benefit is “an incredibly tall order” (p. 159).

Chapter 10: Fragility amplifiers

The fragility touched upon above partly results from gaps in the protection of digital networks. Ransomware attacks can wreak havoc in many areas of public life that operate on digital bases: airports, hospitals, mass transit rail systems etc. Another factor in creating fragility is that access to power is democratized. In other words, the cost for not only talking but also acting goes down. The next wave will enable people to produce quality content. “AI doesn’t just help you find information for that best man speech; it will write that speech too (p. 164; original italics). Thus, one will not be stuck with one’s ideas but can translate them into texts and other products.[3] This applies to individuals as well as state bureaucracies and business organizations. Yet, “If everyone has access to more capability, that clearly also includes those who wish to cause harm … Democratizing access necessarily means democratizing risk” (ibid.).

Suleyman then deals with various areas where fragility is amplified.

- Robot weapons (drones, etc.), or lethal autonomous weapons” (p. 168). Obviously, “When non-state bad actors are empowered in this way, one of the propositions of the state is undermined: the semblance of a security umbrella for citizens is deeply changed” (ibid.). This leads to the question, “How does a state maintain the confidence of its citizens, uphold that grand bargain, if it fails to offer the basic promise of security?” (ibid.). The fundamental problem with AI and bioagents in this respect is that “without a dramatic set of interventions to alter the current course, millions will have access to these capabilities in just a few years” (p. 169).

- Fake news, deepfake news enabled by AI and accessible by everyone.

- “State-sponsored Info Assaults” (p. 171), not only by Rusia and China. During COVID-19, there was already a “targeted ‘propaganda machine,’ most likely Russian, designed to intensify the worst public health crisis in a century” (p. 172).

- Leaks in laboratories (point in case: the possibility that COVID-19 was caused by a leak in Wuhan, China). This kind of problem is not about people intentionally wishing to do harm. It is about unintended consequences and accidental actions. One peculiar side effect can be that “humans aren’t needed for much work at all” (p. 177).

This issue is about the future of human work, as seen from the perspective of AI-induced automation. Until very recently, “new technologies have not ultimately replaced labor; they have in the aggregate complemented it” (p. 178). This process might become obsolete: “What if a large majority of white-collars tasks can be performed more efficiently by AI? In few areas will humans still be ‘better’ than machines. I have long argued this is the more likely scenario. With the arrival of the latest generation of large language models, I am now more convinced than ever that this is how things will play out” (ibid.). The days of “cognitive manual labor are numbered” (ibid.). And it is improbable that new jobs can be created in the number necessary to compensate for the loss of jobs caused by the application of AI. Who, then, will pay the taxes necessary for keeping state services up and running? The “state, already fragile and growing more so, is shaken to its core, its great bargain left tattered and precarious” (p. 182).

Chapter 11: The Future of Nations

This won’t affect all political systems equally. Rather, democratic political orders will be weakened while authoritarian systems will acquire potent tools to augment the control of their citizens. “The nation-state will be subject to massive centrifugal and centripetal forces, centralization and fragmentation” (p. 185). Overall, there will be a “long-term macro-trend toward deep instability grinding away over decades” (ibid.). Concurrently, the power of states will be challenged by private corporations. The “frontier of this wave is found in corporations, not in government organizations or academic labs” (p. 187f.). “I think we’ll see a group of private corporations grow beyond the size and reach of many nation-states” (p. 188). They will enter spaces left uncovered by weakened states. “In this scenario there will be just a few mega-players whose scale and power will begin to rival traditional states” (p. 190). And they will use their power. “Little wonder there is talk of neo- or techno-feudalism—a direct challenge to the social order…” (p. 191) and the nation-states. As mentioned, regarding authoritarian states, their capacity for surveillance will increase enormously. What is to come can already be seen in China where surveillance is a key research area concerning AI. The “prospect of totalitarianism [has risen] to a new plane” (p. 196). Yet, there is also the possibility that AI tools will have the effect of fragmentation when access to AI tools and their usage becomes easy for everyone. “These heralds a colossal redistribution of power away from existing centers” (p. 199, original italics). “Hyper-libertarian technologists like the PayPal founder and venture capitalist Peter Thiel celebrate a vision of the state withering away, seeing this as liberation for an overmighty species of business leaders of ‘sovereign individuals,’ as they call themselves” (p. 201). This might be an extreme ideology, but the tension of centralization and decentralization remains real enough. “Everyone can build a website, but there’s only one Google. Everyone can sell their own niche products, but there’s only one Amazon. … The disruption of the internet era is largely explained by this tension, this potent, combustible brew of empowerment and control” (p. 203).

Chapter 12: The dilemma

The author reminds readers that the new technology will improve the lives of innumerable people. However, there could also be catastrophes. So, this chapter serves as a warning about this danger, ranging from AI-enabled weapons to engineered pandemics, AI machines taking steps to empower themselves, or hacker attacks on energy grids, hospital operations, financial institutes, or mass transit operations. The risk of enabling authoritarian states has been mentioned already. “AI is both valuable and dangerous precisely because it’s an extension of our best and worst selves” (p. 210), which includes “cults, lunatics, and suicidal states” (p. 212). What, then, is the “dilemma” referred to in the title of this chapter? It is that “The costs of saying no are existential” while “every path from here brings grave risks and downsides” (p. 221). “Over the last decade or so this dilemma has become even more pronounced, the task of tackling it more urgent. Look at the world and it seems that containment is not possible. Follow the consequences and something else becomes equally stark: for everyone’s sake, containment must be possible” (p. 222, original italics).

Chapter 13: Containment must be possible

One thing seems to be certain: The standard answer—“regulation”—is vastly insufficient, because regulators do not have the capacity to keep up with the technological evolution. It is rather doubtful whether the recently passed AI Act of the European Union (EU) will be up to the task of not only protecting people from adverse effects but also promote AI-related research and its adoption in the EU. When the authors were writing their book, this regulation was still in the process of passing it into law. See their remark on page 229 where they say, “It has been attacked from all sides, for going too far or not going far enough. … Some believe it lets big tech companies off the hook, that were instrumental in its drafting and watered down its provisions. Others think it overreaches and will chill research and innovation in the EU, hurting jobs and tax revenues.” A principal problem here is that the EU is a territory in competition with other territories. If it puts limits on AI research, development, and application while other territories do not, it might put the EU at a disadvantage, Moreover, the kind on regulation can be quite different. For example, “Chinese AI policy has two tracks: a regulated civilian path and a freewheeling military-industrial one” (p. 231).

Chapter 14: Ten steps toward containment

The ten steps are as follows:

- Safety: “An Apollo program for technological safety.”

- Audits: “Knowledge is power; power is control.”

- Choke points: “Buy time.”

- Makers: “Critics should build it.” The makers of technology bear “responsibility for their creations” (p. 252).

- Business: “Profit and purpose.” “When it comes to exponential technologies like AI and synthetic biology, we must find new accountable and inclusive commercial models that incentivize safety and profits alike. It should be possible to create companies better adapted to containing technology by default. I and others have long been experimenting with this challenge, but to date results have been mixed” (p. 254).

- Governments: “Survive, reform, regulate.” It is hard to regulate when one does not understand the object. Therefore, governments must get involved in AI research and in building technology. They need to nurture “in-house-capability.” This will be expensive, but it will help dealing with these issues appropriately (p. 259).

- Alliances: “Time for treaties.” (international cooperation)

- Culture: “Respectfully embrace failure.” “Containment can’t just be about this or that policy, checklist, or initiative, but needs to ensure that there is a self-critical culture that actively wants to implement them, that welcomes having regulators in the room, in the lab, a culture where regulators want to learn from technologists and vice versa” (p. 269).

- Movements: “People power.” (public input)

- The narrow path: “The only way is through.” This final step is about the coherence of all containment measures. They are to be managed as an “emergent phenomenon of their collective interplay” (p. 275). “Containment is not a resting place. It’s a narrow and never-ending path” (ibid.). “The narrow path must be walked forever from here on out, and all it takes is one misstep to tumble into the abyss” (p. 278).

“The coming wave is going to change the world. Ultimately, human beings may no longer be the primary planetary drivers, as we have become accustomed to being. We are going to live in an epoch when the majority of our daily interactions are not with other people but with AIs. This might sound intriguing or horrifying or absurd, but it is happening” (p. 284).

MHN

Nonthaburi, Thailand

5 January 2025

[1] Since Suleyman wrote this, the influential tech minority around Peter Thiel and Elon Musk got their favorite candidate elected president of the United States of America: Donald Trump.

[2] In this series, see the summary of Angus Deaton. 2023. Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

[3] In a recent newspaper article, a university student felt bad about the grading of his paper. He had used the help of AI to improve it and now thought that the grade did not reflect his own capabilities but rather that of the AI tool he had used.

Leave a comment