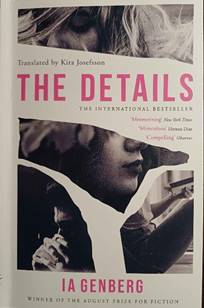

Ia Genberg. 2024. The Details. Translated by Kira Josefsson. London: Wildfire. 151 pp.

Jente Posthuma. 2023. What I’d Rather Not Think About. Melbourne, London, Minneapolis: Scribe. 203 pp.

All three books were among those six shortlisted for the 2024 International Booker Prize. I suggest them together because they are rather short at 93, 151, and 201 pages.

Only the first of these books, Selva Almada’s Not a River, has an underlying story. Two friends, Ernero and El Negro go on a fishing trip to an island that is in a river flowing through an unnamed place in the Argentine countryside. They take along Tilo, who is the son of Eusebio, a former friend who drowned in the river on a previous fishing trip. After a hard fight, their catch is a big ray. When they are back in their camp, some local men come and admire it. They seem friendly enough. However, Ernero and El Negro are not sure what to do with it and end up throwing the dead fish back into the river. When the group of local men find out that the ray was killed for nothing, they become very angry and decided that these townspeople need to be “taught a lesson.” While Ernero, El Negro, and Tilo are at a local dance, the group of local men destroy their camp and set it on. They then beat them up at the dance. As they flee the scene, Ernero, El Negro and Tilo are helped by two girls who actually had died in a car accident earlier in the story already. Alcohol and cigarettes are important elements in the lives of the protagonists.

Almada’s text, while having an underlying story, is not arranged in a simple chronological line. Rather, it consists of short sections interwoven with events that occurred earlier. Thus, as the story progresses, its narrative is interrupted by flashbacks, such as that of the drowning of Tilo’s father, Eusebio, twenty years ago, and many others, both of this group of friends and of the group of local men, such as the circumstances of the deaths of the two girls who would later help them escape.

Ia Genberg does not offer a plot in her novella The Details. She presents the reader with four characters that her bisexual protagonist, who lives in urban Sweden, has met in her life and who have left a lasting impression on her: Johanna, Niki, Alejandro, and Birgitte. With Johanna, the protagonist lived in a lesbian relationship for many years, while the relationship with Niki was more like a flat-sharing arrangement. The part about Alejandro starts with this introduction:

Right when I wanted a hurricane there was a hurricane. I had longed to be swept off my feet, to get entangled in something, and I had the good luck of getting exactly what I’d asked for, the bad luck of getting everything I thought I wanted, the good luck and the bad luck of having my prayers about passionate love heard. (p. 85)

The last section is about the protagonist’s mother, Birgitte, a person troubled by anxiety. At the beginning of this section, there are remarks that perhaps relate to the approach mentioned in the title of the book—The Details:

… it might be one way of describing the whole, people filing in and out of my face in no particular order. No ‘beginning’ and no ‘end’, no chronology, only each and every moment and what transpires therein. (p. 123)

This seems to be a good description of the way Ia Genberg has written this book. It is to her credit that reading this text does not lead to boredom, but to curiosity about what will happen next, what the next “details” will bring.

Jente Posthuma’s book What I’d Rather Not Think About is about the twin sister of a gay brother who suffered from severe depression and eventually committed suicide. This event shocks her deeply and leads to a seemingly never-ending stream of reflections about her brother, their relationship, and her own personality. For some time before his death, her brother had become increasingly distant from her, and she had tried very hard to reconnect with him. But that ended with the following vignette:

I was sitting on the sofa with a book when my mother called. Leo [the friend with whom she lived together] was at the supermarket.

Your brother’s gone, she said. He took the folding bike and left a note.

I asked what she meant.

He’s gone, my mother repeated.

He’d also left a map – a Google Maps satellite photo with an ‘X’ marked at the spot where the river forked, where the water was widest and deepest. That’s where she sent the police.

The second time she called to tell me they were dredging the river. And the third time she said: He’s dead.

I stood at the window, looking at the houses on the other side of the park. I’m always afraid you’ll get mad at me, he’d recently confessed. His voice had sounded calm, unhurried. And I’d been so relieved, happy to connect with him again, however briefly. (p. 123)

Her brother’s apartment was across the park in a Dutch city. She went there to clear out his things but seemed unable to let go. Even 2 ½ years after her brother’s death, she spent most of her time and nights in his apartment rather than in the apartment she shared with her boyfriend, Leo. Near the end of the book, even her understanding and patient boyfriend seemed to have lost hope that their relationship could be rebuilt against the overwhelming force of the grief the sister felt over her brother’s death.

MHN

Nonthaburi, Thailand

3 June 2024

Leave a comment