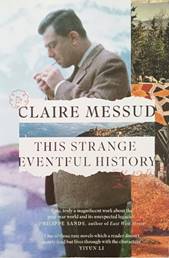

This novel tells part of the story of Claire Messud’s family in fictionalized form. It is a massive text filled with dense atmospheric prose (sometimes, I could not help thinking that fewer words would have been better) and occasional dialogues. Her writing style captured my attention, and I very much looked forward to my daily dose of pre-bedtime reading. Yet, this is not an easy text because readers witness an utter alienation of two people who had once loved each other so much that they would take the risk of marrying each other, though they were from very different backgrounds, indeed. These two people are the fictionalized parents of the author, called François and Barbara in the novel. They have two daughters, Chloe (Claire) and Loulou.

François and his younger sister Denise were born to French-Algerian parents, Gaston and Lucienne (who was the youngest sister of Gaston’s mother). Their marriage was extremely happy, and they shared the “certainty that this love [was] their life’s masterpiece” (p. 421). To Françoise, his parent’s relationship seemed to have been the model that he hoped to replicate in his own marriage. The family considered Algier their home. But Algeria was part of France’s colonial possessions. So, this home could not last. The French and their indigenous helpers had to leave the country when it gained independence in 1962. Both groups had to relocate to France, were neither group was welcome.

François received a Fulbright scholarship to study at Amherst. He later almost completed his Ph.D. at Harvard University with a thesis on politics in Turkey. “Almost,” because he thought that had to choose between realizing his dreams and becoming the provider for Barbara and his family. He met Barbara—a Canadian from Toronto who could never imagine a life outside of this city, least of all in the United States where they finally ended up—at a summer school at Oxford. Years later, in 1998 at age 65, Barbara reminisced:

She’d been a constant disappointment, then, simply for being herself. But he still loved her, or claimed to, whereas she—well. She’d say that she did still love him, whatever that meant—just about. She cared for him, and worried about him, and felt pity for his suffering, and wished she could take away his pain. But she believed, wholeheartedly, that this had all been a mistake, that if she could call back in time to the girl she had been, dazzled by the dashing Frenchman on the bus in the rain at summer school at Oxford, she would say: “Don’t! Don’t do it. Walk away. Go home. … take the job at the Globe and Mail, and cling to it with all you’ve got. But whatever you do, don’t marry him. … No point imagining a life that wasn’t. There was plenty of good in this one, even with the glass half empty. And the kids—she couldn’t imagine her life without the kids. (p. 340, original italics)

François, on the other hand, had hard feelings too. Almost ten years earlier, he thought to himself:

All he’d ever wanted was to love and to be loved, to have the mirror perfection of his parents’ marriage. Even after all the years, so many arguments and harsh words, so many recriminations, so much disappointment, he kept trying: Barb was the love of his life, he’d never doubted it; he couldn’t believe, not really, that she thought their life together had been a terrible mistake. (p. 292)

In 1998, he accepted that his original family was sort of a home to him. However:

How to convey that even if he could belong to them, he needed not to; or, rather, he needed to find somewhere else or someone else to belong to; and that there, of course, lay the greatest sorrow, that Barbara did not, could not open her arms to him. She could not give him home. (p. 353)

Yet, the time when either of them could or would seriously consider divorce was long gone. What sense did it make to divorce at age 65 and 67? Thus, they stayed together, living out their retirement in Connecticut until he died of cancer in 2010. By that time, Barbara barely recognized him any longer because she had developed serious dementia that had started several years earlier.

MHN

Nonthaburi, Thailand

12 June 2025

Earlier brief descriptions of books in this series:

Anne Berest. 2023. The Postcard. A Novel. New York Europa Editions. 475 pp. The original French publication appeared in 2021, entitled La card postale, at the Editions Grasset & Fasquelle. It was translated by Tina Kover.

Michael Frank. 2023. One Hundred Saturdays: Stella Levi and the Search for a Lost World. Artwork by Maira Kalman. London: Souvenir Press. 215 pp.

Filip Müller. 1979. Eyewitness Auschwitz: Three Years in the Gas Chambers. Literary collaboration by Helmut Freitag. Edited and translated by Susanne Flatauer. New York: Stein and Day. New German edition 2022, Sonderbehandlung: Meine Jahre in den Krematorien und Gaskammern von Auschwitz. Deutsche Bearbeitung von Helmut Freitag. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. 320 pp.

Angus Deaton. 2023. Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. 271 pp.

Charlotte Wood. 2019. The Weekend. A Novel. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. 262 pp.

Ivan Krastev and Stephen Holmes. 2019. The Light that Failed: Why the West is Losing the Fight for Democracy. New York: Pegasus Books. 247 pp.

Laurent Mauvignier. 2023. The Birthday Party. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions. 499 pp. French original Histoires de la nuit, Les Editions de Minuit, 2020. Translated by Daniel Levin Becker.

Margaret O’Mara. 2019. The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. New York: Penguin Press. 496 pp.

Christopher R. Browning. 2005. The Origins of the Final Solution: The Evolution of Nazi Jewish Policy, September 1939—March 1942. With contributions by Jürgen Matthäus. Published by the University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, and Yad Vashem, Jerusalem. London: Arrow Books.

615 pp.

Celeste Ng. 2022. Our Missing Hearts. London: Abacus Books. 335 pp.

Ingeborg Rapoport. 2021. Meine ersten drei Leben: Erinnerungen. [My First Three Lives: Memoirs.] Berlin: Bild und Heimat. 415 pp. First pocketbook edition 2002. Original edition 1997.

Jan-Werner Müller. 2022. Democracy Rules. Penguin Books. xvi+236 pp.

Seichō Matsumoto. 2022 [Third edition 2023]. Tokyo Express [Ten to Sen, Points and Lines]. Translated by Jesse Kirkwood. Dublin: Penguin Books. 149 pp.

Itamar Vieira Junior. 2023. Crooked Plow. Translated by Johnny Lorenz. London and New York: Verso. 276 pp. Originally published in Brazilian Portuguese in 2018, entitled Torto Arado.

Heather Cox Richardson. 2023. Democracy Awakening: Notes on the State of America. London: WH Allen. xvii+286 pp.

Celeste Ng. 2017. Little Fires Everywhere. A Novel. New York: Penguin Press. 338 pp.

Paul Lynch. 2023. Prophet Song. London: Oneworld Publications. 309 pp.

Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. 2023. Tyranny of the Minority: How to Reverse an Authoritarian Turn and Forge a Democracy for All. Dublin: Viking. 388 pp.

Luke Jennings. 2018. Killing Eve: Codename Villanelle. London: John Murray. 217 pp. (Originally published in serial form in 2014.) Volume 2: No Tomorrow. London: John Murray. 2018. 248 pp. Volume 3: Die For Me [UK: Endgame]. London: John Murray. 2020. 228 pp.

Adelle Waldman. 2024. Help Wanted. A Novel. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. 276 pp.

Selva Almada. 2024. Not a River. Translated by Annie McDermott. Edinburgh: Charco Press. 93 pp. / Ia Genberg. 2024. The Details. Translated by Kira Josefsson. London: Wildfire. 151 pp. /

Jente Posthuma. 2023. What I’d Rather Not Think About. Melbourne, London, Minneapolis: Scribe. 203 pp.

Jenny Erpenbeck. 2024. Kairos. Translated by Michael Hofmann. New York and London: New Directions (W.W. Norton). 304 pp. German original: Kairos. Roman. München: Penguin Verlag. Original edition 2021, softcover 2023. 379 pp.

Paul Murray. 2024. The Bee Sting. London: Penguin Books. 645 pages. First published in 2023 by Hamish Hamilton. Shortlisted for the Booker Prize 2023. 643 pp.

Charlotte Wood. 2023. Stone Yard Devotional. London: Sceptre. 297 pp.

Samantha Harvey. 2024. Orbital. Dublin: Vintage. 136 pp.

Yael Van Der Wouden. 2024. The Safekeep. A Novel. Dublin: Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books. 262 pages.

Rachel Kushner. 2024. Creation Lake. London: Jonathan Cape. 407 pp.

Anne Serre. 2023. A Leopard-Skin Hat. Translated from French by Mark Hutchinson. London: Lolli Editions. Originally published by Éditions Mercure de France in 2008 as Un chapeau léopard. This English translation first published as New Directions Paperbook 1574 in 2023. 136 pp.

Vincenzo Latronico. 2025. Perfection. Translated by Sophie Hughes. London: Fitzcarraldo Editions. 113 pp.

Dahlia de la Cerda. 2024. Reservoir Bitches. Translated by Heather Cleary and Julia Sanches. Melbourne, London, Minneapolis: Scribe. 184 pages

Miranda July. 2024. All Fours. New York: Riverhead Books. 326 pp.

Liz Moore. 2024. The God of the Woods. London: The Borough Press. 435 pages

Slavoj Žižek. 2023. Freedom: A Disease Without Cure. London et al: Bloomsbury Academic. 320 pages

Onyi Nwabineli. 2024. Allow Me to Introduce Myself: Her Life. Her Rules. Finally. London: Magpie Books. 313 pages

Leave a comment