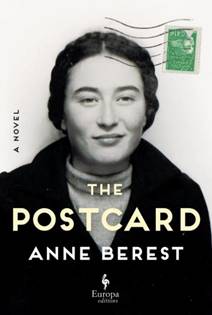

475 pp. The original French publication appeared in 2021, entitled La card postale, at the Editions Grasset & Fasquelle. It was translated by Tina Kover.

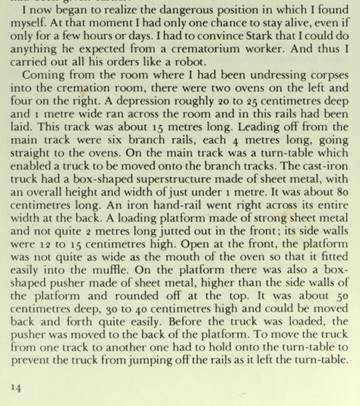

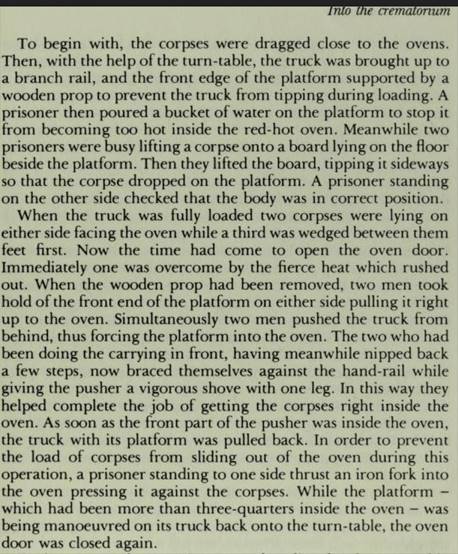

Though the book is called a “A Novel,” the four names on the postcard—Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie (it is her picture on the dust cover) and Jacques—are not fictional characters. Rather, the first names refer to the author’s great-grandparents, while Noémie and Jacques (Itzak, Isaac) were two of their three children. All of them died in the Auschwitz concentration camp in the autumn of 1942. The children were rounded up in July 1942 (this round targeted foreign Jews living in France) by French police and German soldiers and sent to the Pithiviers internment camp. This was a transit camp before the prisoners were sent to Auschwitz. Noémie and Jacques were put on convoy no. 14 that left on 3 August 1942 and arrived on 5 or 6 August 1942. Jacques, being only 16 years old, was murdered in the gas chambers on arrival (as were 482 other people of the 1023 people on the convoy). During the “selection” (to me personally, the German “Selektion” has become to symbolize the Holocaust, and to this day, I feel very uncomfortable when this word is spoken) on the ramp of the extermination camp, 19-year-old Noémie was seen as being fit enough to serve the Germans as slave laborer, as were 541 other women and 22 men. Yet, she died on 6 September 1942 of typhus (as the author mentions on page 189). Around that time, a typhus epidemic had existed in Auschwitz for some time. For the day of Noémie’s death, the Sterbebücher (Books of Death, kept as records by the German authorities for those who were registered inmates; her brother is undocumented because he was murdered right away) record the death of altogether 266 inmates.

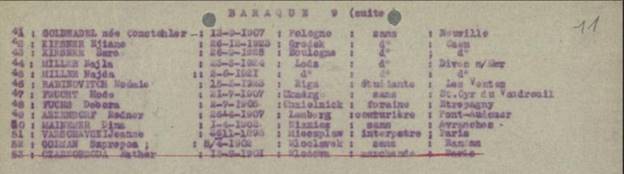

Noémie’s name on the deportation list from Pithiviers to Auschwitz.

Source: https://www.memorialdelashoah.org/

Sources for the pictures and documents can be found in the links listed at the end.

As an aside, I wondered about why the dates of death for Noémie’s and Jaques (as well as for other Jews who had lived in France) often had the remark (in French) “and not on the 2 of August 1942 in Pithiviers (Loiret).” Had it been assumed that they had died in the transit camp? No. Rather, the French government at the time did not accept their death in Auschwitz. Accordingly, to the civil courts issuing the death certificates after the war and Nazi occupation the “official death dates were the days the deportation convoys left France” (p. 256). Ephraïm (born 1890 in Penza, Russia) and his wife Emma (born 1892 in Lodz, Poland) were sent in convoy no. 40 from the internment camp in Drancy to Auschwitz on 4 November and died in the gas chambers on 9 November 1942. At their age, they were of no use to the Germans.

Ephraïm, Emma, Noémie, and Jacques Rabinovitch

After the war and the Nazi regime had ended, Myriam (born in 1920), the eldest daughter of Ephraïm and Emma, and the only surviving member of this family, filled in the form of the French authorities searching for missing members of one’s family (at that time, she had been married already, and thus referred to herself as Madam Picalia; after her second marriage, her name was Myriam Rabinovitch-Bouveris). This is the form for Noémie:

In 1989, the uncle of Noémie and Jacques, Jacques Bouveris (the son Myriam had with Yves; he does not play any role in this novel), submitted testimonies to Yad Vashem about the four family members who were murdered by the Nazis. In facsimile, this is the testimony about Noémie:

This concludes the brief description of the historical/biographical excursus. I will now turn to give a description of the novel.

The novel is divided into four “Books.” Characteristically, the first one (pp. 11-196) is called “Promised Lands). It tells the story of the Rabinovitch family, mostly the part headed by Ephraïm, of trying to find a country in which they could live, develop roots, and fulfill their dreams of belonging, only to end up being murdered in the Nazi’s extermination camp of Auschwitz (apart from the eldest daughter, Myriam).

Anne Berest starts the narrative with her being with her mother, Lélia, in early January of 2003. The postman brought the mail, mostly from people wishing them a Happy New Year. But there was also something strange—a postcard with an outdated picture of the Opéra Garnier. It had no signature and no text, only a list of four names in an unknown handwriting: Ephraïm, Emma, Noemie, Jacques. The posts stamp showed that the card was mailed at the Paris Louvre post office on 4 January 2003. Anne was pregnant with her daughter at that time. What follows is a mix of information that her mother tells her about their ancestors (she had done a great deal of research of happened to them during and after World War II and the Nazi occupation) and a more extensive part of descriptions and dialogues that provides the fictional backbone of this chapter.

At a family meeting in a Russian dacha on 18 April 1918, the father of Ephraïm informed his children that he would move to Palestine, and he urged them to move out of Russia too. Nachman Rabinovitch saw the signs of post-revolutionary danger: “The evening had been so pleasant, the siblings uniting in gentle mockery of their father. The Rabinovitches had no way of knowing that these were the last hours they would all spend together as a family” (p. 27).

Shortly after Myriam was born in Moscow on 7 August 1919, Ephraïm’s small family fled the Bolshevik’s crackdown on former allies to Riga. He started trade in caviar. “But Ephraïm the engineer, the progressivist, the cosmopolitan, had forgotten that an outsider will always be an outsider. He’d made the terrible mistake of believing that he could rely on happiness in any one place … These immigrants arriving in their wagon had become too successful, too quickly” (p. 37). His business went bankrupt, possibly through foul play of his competitors. The family had to flee again, ending up in Palestine, where is father, Nachman, operated an orange farm that was in financial trouble. Itzhak/Isaac/Jacques was born in Haifa in 1925. Ephraïm could not stand the hot weather and leading a life with no real purpose. After five years in Palestine, the family moved to Paris in 1929.

Soon enough, news became worrisome again, because, in 1933, the Nazis came to power in neighboring Germany, and Ephraïm’s dream of achieving French citizenship for his family remained unfulfilled. To the French, they remained stateless Jewish immigrants (that is, that category of Jews targeted in the first round-up of Jews in 1942). Nevertheless, their daughters excelled at school with Myriam moving on to study philosophy at the Sorbonne. On 23 June 1940, Hitler paraded his troops in Paris. Jews had to register with the French authorities. In mid-June, the sisters learned that a numerus clausus would be enacted to limit the number of Jews at French universities. Meanwhile, Emma’s parents in Lodz, Poland, became prisoners when the Nazi occupation forces turned their district of the city into a Jewish ghetto in April 1940. Myriam married Vicente Picabia in November 1941. When the situation became too dangerous, in a daring move, his mother and sister smuggled her into the “free” zone of France. Noemie and Jacques (but not their parents) were arrested in July 1942 and, first, sent to Vél d’Hiv, a sports stadium, and then, on 17 July, to the Pithiviers transit camp. On 2 August, they were put on a train of cattle wagons. They had to stay in it for the night, because the trip would only start on the following day. On 8 October 1942, police came to arrest Emma and Ephraïm. “Emma and Ephraïm were gassed immediately after arriving at Auschwitz, during the night of November 6-7, because of their ages: fifty and fifty-two” (p. 193). Thus, by this time, this branch of the Rabinovitch family had almost entirely died by state-organized mass murder. Only Myriam survived (on her, see below).

Admittedly, I have emphasized the historical account in these lines, although the text is written mostly in the form of a novel. Anne Berest does so in such a captivating and moving way that I was hard-pressed to interrupt my reading when bedtime had come during the evenings that I spent with this book. Looking at Noémie’s picture on the dust cover has become painful given to what happened to her young and promising life, and to the life of her family.

Book II covers pages 197 to 317. Anne consults a private detective about the card and a graphologist too. Neither can help her very much. The “Books’s” title, in fact, is “Memoirs of a Jewish Child Without a Synagogue.” The question of Anne’s Jewishness comes up when her daughter returns home from school and tells her mother, “They don’t like Jews very much at school.” This leads to a reflection about Anne’s own Jewishness. She had told her new love interest, George, who is Jewish, that she is also Jewish. So, he invites her to celebrate Pesach with family and friends. It is only when she attends that gathering that George realizes that Anne does not know anything about Jewish religious customs and can neither speak, read, or understand Hebrew. To her, being in that gathering is like being in an entirely foreign cultural environment. She also admits never in her live having been in a Synagogue because she was brought up in an entirely secular, socialist-progressive-humanistic environment. She is Jewish in name only, although she did, over the years, have a few experiences with being Jewish. But since her looks, name, and surname are as French as it could get, people with whom she interacted never really could put her into this ethno-religious category and thus had no occasion to activate their respective prejudices and their verbal reflections towards her. In turn, not being exposed to such reactions prevented her from developing a distinctly Jewish identity. To George, Anne says (on p. 253; italics in the original):

You know … all my life, I’ve had trouble actually saying the words ‘I’m Jewish.’ I never felt like I had the right to say it. And … its weird, but it’s almost like I’d taken on my grandmother’s fears. In a way, the secret Jewish part of me was glad to be hidden by the goy part. Made invisible. No one would ever suspect me. I’m my great-grandfather Ephraïm’s dream come true. I’ve got a perfectly French face.

The detective part of the story continues with Lélia and Anne visiting the village in which the Rabinovitches had a house before their deportation. Myriam sold it soon after the war. The current owner tells them that many things were stolen by fellow villagers before she moved in. While still driving in the village, Lélia’s phone rings. It is an anonymous caller who informs them in which house they can find Emma Rabinovitch’s piano. Under a pretext, the owner lets them in. Right in the living room: Emma’s piano! Without knowing who his visitors are, the owner gives them a shoebox with old photographs (they had told them that they looked for old photographs from the 1930s), mostly showing the house of the Rabinovitch family. After having seen the piano, Lélia and Anne are already in emotional distress. This becomes much worse when, among the photographs, they discover a picture showing Jacques with Nachman, standing next to their newly dug well. Lélia starts crying, and their host cannot comprehend what is going on, though he had become a bit suspicious when mother and daughter showed their interest in the piano. After they left the house (not without Lélia having stuffed several of the photographs into her handbag) and returned from the village bakery, they found a manila envelope placed under the windscreen wiper of Lélia’s car. It contained four postcards written in 1939 in Russian to Ephraïm’s address in Paris. They were sent from Prague by his brother, Boris. He was shot in the back of his head in 1942, lined up in front of the pits at the extermination camp of Maly Trostenets near Minks in Belorussia.

“Book III – First Names” is only eight pages long. In them, the sisters Anne and Claire reflect about the influence of their second names (Myriam for Anne, and Noémie for Claire) on their lives and their relationship.

Book IV (pp. 329-475) is headlined “Myriam.” This section is about Myriam’s life after she was smuggled into the “free” area of France, her life afterwards, her ill-fated marriage to Vicente Picabia (the father of Anne’s mother, Lélia), and what led to her second marriage to Yves Bouveris, after Vicente had died of a drug overdose. Until her death at 75 in 1995, Myriam strictly avoided speaking about her experiences, her thoughts, and her memories, though Anne spent many summer holidays in her house in a small village. Once, her mother asked Myriam, in the presence of Yves, whose daughter she actually was, that of Vicente or Yves. Myriam was very upset. However, after a few days, a letter from her arrived explaining what had happened. Lélia also receives a letter with a thick envelope from the staff in the town hall of the village where the Rabinovitch family lived before their deportation. They had found it in the office’s archive. She does not dare open it but allows Anne to do so. It contains one notebook written by Noémie and the beginning of her novel.

When Anne and George visit the village where she stayed so often in her grandmother’s house, the mystery of the postcard is finally solved in an undramatic, but touching, way. She also relates to three events, the latest concerning her daughter (mentioned above), in 1925, 1950, and 2019, when the family’s children were confronted by their Jewishness. When this happened,

For the children of Céreste, like the children of Lodz—and the children of Paris in 2019, for that matter—it was nothing more than a joke, a schoolyard taunt like any other. But for Myriam, and Lélia, and Clara, it was an interrogation. … What does it mean to be Jewish? Maybe the answer was contained within another question: What does it mean to wonder what it means to be Jewish? (p. 455 f.; italics in the original)

Links:

DEPORTED DEATHS BORN IN FRANCE (lesmortsdanslescamps.com)

Isaac-Jacques RABINOVITCH was born on December 14, 1925, in Haifa. His older sister, Noémie, age 19, was born in Riga, Latvia. They were deported on convoy 14 of August 3, 1942, after having been arrested in Les Ventes (Eure), west of Paris. Jacques is shown in this picture, taken around 1930, with Myriam, his oldest sister, who escaped deportation.

Sterbebuecher Excel file

Transport 16 from Pithiviers, Camp, France to Auschwitz Birkenau, Extermination Camp, Poland on 07/08/1942

Link to data from the camp where Noemie and Jacques were interned in France.